Development and Disaster: Urban Places

As weather events increasingly become more costly and destructive, understanding the relationship between development and disaster can help make smart building decisions, minimizing risks, and subsequent costs, of future disasters. This article is the second in our series, Development and Disaster, where we examine the impact of land use and development on how we, as a society, experience disasters.

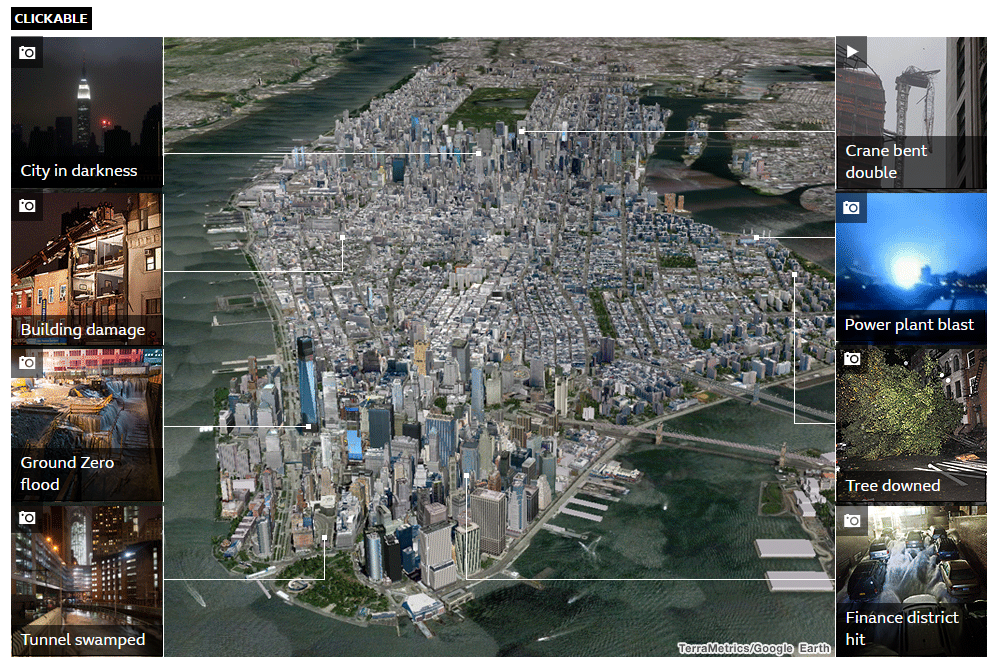

According to the 2020 Census, more than 265 million people (nearly 80% of the US population) live in urban places, which are generally defined by both increased population size and density. Within a large urban area, disaster impacts can cascade rapidly out of control, potentially endangering millions while simultaneously disrupting the public safety networks, transportation systems, and other critical infrastructure designed to support large metropolitan areas. Cascading failures due to interdependencies between complex infrastructure and utility systems (especially power, water/sewer, and communications) can profoundly complicate response and recovery operations.

Once those systems fail, public officials and emergency managers in urban areas must contend with high population density, aging infrastructure, their city’s unique geographic concerns, and still coordinate (hopefully effectively) with each level of government above and below them.

Geography

America’s cities are growing, and this growth increases the stressors on America’s already-aging infrastructure. According to the National League of Cities, the total land area of the United States’ ten largest cities nearly doubled between 1920 and 2020. Within these urban places, the close proximity of buildings and confined space contributes to a unique mosaic of challenges for disaster response in urban places; including urban flooding, the urban heat island effect, emerging technological hazards, seismic hazards, and novel acts of terrorism, just to name a few.

All emergency plans contain certain assumptions that critical services will fail to some degree. It is only after a disaster that a community discovers whether a plan, as written, can be implemented. Sometimes, pre-determined evacuation routes are not accessible. Locations for staging areas, shelters, debris management sites, points of distribution for water and ice… all of those may need to be re-evaluated.

Population

Urban places, by definition, imply more people are vulnerable to the full range of natural and man-made hazards. It also infers that more people may require evacuation, rescue, medical care, or other emergency services. High-density populations also intensify the risk of secondary humanitarian crises which can divert, distract, or dilute critical public safety resources. Conversely, a larger population also provides the potential for more capacity, with more human and financial resources available to support response, short-term and long-term recovery.

The co-location of major transportation corridors and close proximity to transportation hubs (airports, train/bus stations, subways) simplifies some logistics, particularly during evacuations, but the infrastructure we rely upon for these logistics sometimes fails. When that happens, public safety officials and emergency managers adapt, improvise, and change their plans to meet current conditions and new realities.

Resources

Urban places generally possess much larger tax bases than their rural counterparts and consequently, they generally operate with much larger budgets. Grant distribution formulas for pre- and post-disaster grants are often population based, and by design tend to favor densely populated areas.

FEMA’s State Homeland Security Programs (SHSP) and Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI) are examples of grant programs that are specifically designed for regions with high-density populations. Grant methodologies for both of these programs directly factor population into threat, vulnerability, and consequence calculations, which ultimately affect funding levels.

Other grant programs, too, like FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Assistance Programs and the since-cancelled-but-likely-to-be-reinstated BRIC Program also favor highly populated areas. Awards for these impact-based grants are generally prioritized based on benefit/cost ratios that favor highly populated areas.

Large, at-risk populations who live in urban places underscore the urgency for strong, nonpartisan leaders, who are committed to effective governance. Big City Emergency Managers (BCEM) serves as the primary forum for Emergency Managers from America’s largest cities to meet one another, establish relationships, and pool their collective knowledge and best practices. BCEM member jurisdictions represent the interests of 20% of the US population, residing in 15 of America’s largest, most at-risk metropolitan areas.

We work with Emergency Managers in communities large and small, rural and urban. Some have several staff supporting their offices, and some do the job alone. In order to sustain viable emergency management programs, Emergency Managers require predictable and reliable grant sources. The same is true for rural Emergency Managers, but in urban places with larger organizations and budgets, the stakes are simply higher… and costlier.

SRP Partners’ nonpartisan research enables government and commercial clients to make well-informed decisions and plan for an uncertain future. The Porch is our place to share what we find relevant, interesting, and meaningful throughout the course of our work.